The services rendered at Alabama Nasal and Sinus Center employ the latest technology and techniques. Dr. Sillers, Dr. Lay, and their staff regularly attend training on the latest medical solutions available. Our aim is to provide you the highest level of care, education and research in the area of nasal and sinus diseases. Below is a list of services we provide. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or visit our patient information page.

The services rendered at Alabama Nasal and Sinus Center employ the latest technology and techniques. Dr. Sillers, Dr. Lay, and their staff regularly attend training on the latest medical solutions available. Our aim is to provide you the highest level of care, education and research in the area of nasal and sinus diseases. Below is a list of services we provide. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or visit our patient information page.

Our Services include

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Food Allergies

- Inhalant Allergies

- Immunotherapy (Allergy Shots or Drops)

- Mucoceles

- Nasal Endoscopy

- Nasal Obstruction

- Nasal Polyps

- Sinonasal Tumors

- Smell/Taste Problems

Fungus is present in all our surroundings and in the air we breathe. Most people with an intact immune system do not react to the presence of fungus in the nasal cavity and/or sinuses. However, some people will have an inflammatory reaction to the presence of fungus in the nose and sinuses. Fungal sinusitis can manifest in various forms, differing in pathology, symptoms, course, severity and the treatment required. It is broadly classified into invasive and non-invasive types.

Non-Invasive Fungal Sinusitis

- Fungus ball

- Allergic fungal sinusitis

- Non-allergic fungal sinusitis

Invasive Fungal Sinusitis

- Acute invasive fungal sinusitis

- Chronic invasive fungal sinusitis

- Granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis

Non-Invasive Fungal Sinusitis:

Fungus Ball: This is a non-invasive form of fungal sinusitis. In essence, there is an overgrowth of fungal elements in the sinuses. Most commonly molds such as Aspergillus are responsible. The most commonly involved sinuses are the maxillary and the sphenoid sinuses, where the fungus finds a dark, warm, moist spot favorable for growth. Sometimes, bacteria can cause super- infection in the sinus affected by the fungus ball. Typically, only a single sinus is involved, and the disease has a classic appearance on CT or MRI scans. Treatment involves removal of the fungus ball through endoscopic sinus surgery. Usually a peanut-butter like appearance of the fungal ball mucin is noted. Most patients have excellent results from surgery, and may not require any further treatment.

Allergic Fungal Sinusitis (AFS): Patients with allergy to certain fungi may develop allergic fungal sinusitis. The presence of fungus in the sinuses elicits an allergic response, resulting in production of allergic mucin and nasal polyps. Usually, the disease affects more than one sinus on one side. However, all sinuses on both sides may be involved in severe cases. Patients have a typical appearance on nasal endoscopy with the presence of allergic mucin and inflammatory polyps. Allergy testing to fungi is positive. Sinus CT scans also have a typical appearance. Tissue examination under the microscope shows allergic mucin containing fungal elements without tissue invasion. Treatment involves endoscopic sinus surgery to clear polyps and allergic mucin, and to restore the ventilation and drainage of sinuses. This has to be combined with aggressive medical therapy with corticosteroids which can be used nasally and/ or systemically. Patients may also benefit from treatment of allergy with immunotherapy and antihistamines. Anti-fungal treatment is usually not required, as it is the reaction to the fungus that needs to be modulated. However, in severe recurrent disease, anti-fungal therapy may be needed.

Non-allergic fungal sinusitis: In some instances, mucin and fungus may be identified in patients with sinusitis in the absence of any allergy to fungus. Fungus may also be found in the sinuses of patients that have had previous surgery. Whether these fungi are innocent bystanders or are the cause of sinus disease is currently under investigation and a subject of great debate.

Invasive Fungal Sinusitis:

Acute Invasive Fungal Sinusitis: This is the most dangerous and life-threatening form of fungal sinusitis. Fortunately, it is very rare, and usually afflicts severely immunocompromised patients. These include patients with depressed immunity such as those with leukemia, aplastic anemia, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and hemochromatosis. Patients undergoing anti-cancer chemotherapy or organ/ bone-marrow transplantation are especially susceptible. Aspergillus or members of the class Zygomycetes (Mucor, Rhizopus) are the most frequent causative agents. The disease has an aggressive course, with fungus rapidly growing through sinus tissue and bone to extend into the surrounding areas of the brain and eye. Endoscopically, areas of dead tissue and eschar are noted. Microscopic examination shows invasion of blood vessels by the fungus, causing tissue to die. Treatment involves a combination of aggressive surgical and medical therapy. Repeated surgery may be necessary to serially remove all dead tissue. Medications such as anti-fungal drugs and those that help restore the immune status of the patient are key to improving survival, as this disease is frequently fatal.

Chronic invasive fungal sinus: Unlike acute invasive fungal sinusitis whose typical course is less than 4 weeks, chronic invasive fungal sinusitis is a slower destructive process. The disease causes rare vascular invasion, sparse inflammatory reaction and limited involvement of surrounding structures. It is usually seen in patients with AIDS, diabetes mellitus or chronic corticosteroid treatment. The disease most commonly affects the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses, but may involve any sinus. The typical time course of the disease is over 3 months. Tissue cultures show fungus in over half the patient, and Aspergillus fumigatus is the most commonly grown fungus. Treatment comprises of surgery in combination with medical therapy (anti-fungal drugs and measures to restore the patient’s immune system).

Granulomatous invasive fungal sinusitis: This form of fungal sinusitis is rare in the United States. It is usually seen in patients from Sudan, India, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Patients have normal immune status. The disease has a relatively slow time course over 3 months, and patients present with an enlarging mass in the cheek, orbit, nose, and sinuses. Microscopically, it is characterized by formation of granulomas, and this differentiates it from chronic invasive fungal sinusitis. Aspergillus flavus is usually the causative organism. Treatment may involve surgery in combination with antifungal agents.

Conclusion:

There are many forms of fungal sinusitis. A complete evaluation by your rhinologist will help to determine if you have a form of fungal sinusitis and how it needs to be treated, as some forms of fungal sinusitis have distinctly different medical and surgical treat

Many patients who suffer from allergies have tried every medication on the market at some point and found no relief from their symptoms. Others have gotten some relief with medications, but they do not like the prospect of taking medications every day for the foreseeable future and want to consider immunotherapy. These, and other reasons, motivate us to choose to be tested for allergies.

The classic allergic response is an IgE mediated response of the immune system to a foreign antigen, such as pollen, dust mites, or molds. There are other immunologic reactions that manifest with similar symptoms, like sneezing, nasal congestion, and headache. For the purposes of this article, we will limit our discussion to classic allergy. Allergy testing is a way to determine if you are having an allergic response to a particular antigen. An antigen is usually a protein molecule on some foreign substance. The body recognizes these substances as foreign but not as common environmental contaminants, so the immune system kicks in to mount an attack on the antigen. This immune response can be measured indirectly with a blood test or triggered in a controlled fashion and measured directly with skin testing.

Most people are familiar with skin testing. It is the oldest form of allergy testing. In general, skin testing involves introducing the antigen of interest into the skin and observing the skin for a reaction. The exact technique can vary, but in our office, we use a technique called MQT. First, a skin prick panel is applied to the skin of the forearm or upper arm or back. The skin prick delivers the antigen to the epidermis, or top layer of skin only. There are immune system cells in that layer that will trigger a response if your system is primed to do so. The response is a local wheal, or raised, red bump on the skin. The wheal is measured and recorded. If there is a very brisk reaction, the end point is set at the highest level. The endpoint tells us how dilute to make the antigen in an immunotherapy treatment vial. Less severe reactions require further testing to know where the end point is. This is done by intradermal testing. A small amount of antigen is injected into the dermis, or the deep layer of the skin. The reaction is measured and an end point is reached. Non-reactive scratch tests are taken to mean that those substances are not causing allergy in that patient. The advantage of skin testing is that the results are immediate and a reflection of what actually happens when your body is exposed to an allergen. The disadvantages of skin testing are that the results are influenced by medications which may need to be stopped before testing, and patients with certain skin conditions cannot be tested.

For those who cannot tolerate skin testing or cannot complete skin testing for some other reason, there is the option of doing a blood test (called in vitro testing). In vitro testing has the advantage of being easy for the patient – she only needs to have one needle stick for blood to be drawn. The blood test does not require stopping any medications. The disadvantage of blood testing is that you are measuring levels of reactive immunoglobulin in the blood stream, not a direct response. Sometimes elevated IgE does not correlate to symptoms in the patient. With recent advances in the technology used for in vitro testing, the correlation between blood and skin testing results is much better and we generally consider the tests to be equivalent.

A discussion with your physician can clarify if allergy testing is for you and together you can use the results to craft a treatment plan that works for you.

A disruption in the brain lining (known as the dura) and the bone separating the brain and the sinuses will result in the drainage of fluid that normally surrounds the brain into the sinuses. This fluid is known as cerebrospinal fluid or “CSF.” Drainage of CSF into the sinuses can result in a multitude of problems, not to mention the often times annoying constancy of nasal dripping.

Cerebrospinal fluid consists of a mixture of water, electrolytes, glucose, amino acids and various proteins. Cerebrospinal fluid is colorless, clear, and typically devoid of cells. CSF leaks fall into two basic categories: spontaneous CSF leaks and CSF leaks that occur because of a defect or injury in the bone separating the brain and the sinuses (known as the skull base). These include CSF leaks that are traumatic, caused by surgery and by tumors.

Penetrating and closed-head trauma cause 90% of all cases of CSF leaks. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea following a traumatic injury can occur immediately or up to three months later.

Surgical trauma can occur during endoscopic sinus surgery or during neurosurgical procedures. These injuries occur along the skull base. These injuries vary from simple cracks in the bony architecture to large defects with potentially injury to the brain.

In uncommon cases, aggressive tumors and cancers either erode or invade the bone of the skull base. The breakdown or destruction of the bone results in disruption of these barriers.

Spontaneous CSF leaks occur in patients without any of the previous causes discussed. Recent evidence has led us to realize that spontaneous CSF leaks are probably due to elevated intracranial pressure. The causes of elevated ICP can be multiple; nevertheless, once elevated ICP develops, the pressure exerted on areas of the anterior skull base result in thinning of the bone. Ultimately, the bone is weakened until a defect if formed and a leak begins. The dura or part of the brain may actually protrude through the weakened until a defect is formed and a leak begins. The dura or part of the brain may actually protrude through the weakened part of the bone.

The presentation of a CSF leak is typical: Clear, watery discharge that often occurs only on one side of the nose. Often the discharge is continuous, but it may be sporadic and related to certain activities. This drainage may be reproducible by bending over or by straining. Patients may report a metallic or salty tast. Many patients with spontaneous leaks often are diagnosed with allergies or sinus infections and are unsuccessfully treated, often for many months, with antihistamines, nose sprays, and antibiotics.

Patients with recurrent meningitis should be evaluated for CSF leaks, regardless of the presence of active clear nasal discharge.

A history of headache, ringing in the ears and blurry vision may suggest increased intracranial pressure. In these patients, MRI and CT may reveal signs of increased ICP.

Physical exam includes a complete head and neck examination. Nasal endoscopy is very helpful, especially in a patient who has undergone sinus surgery. Examination may reveal clear discharge, a skull base defect or a mass, such as a neoplasm or encephalocele. In many cases, however, physical examination and nasal endoscopy, are normal and the physician must base his or her decision on history alone.

There are a number of laboratory and imaging studies that can be ordered to confirm the presence of a CSF leak. Testing the drainage for Beta-2 transferrin, a protein found exclusively in CSF, is the most common laboratory test. A high-resolution CAT scan is the best form of diagnostic imaging for identifying a CSF leak. By injecting contrast into the spinal canal, CT cisternography can show the precise location of a CSF leak in most patients who have active clear nasal drainage.

Management of CSF leak is determined in part by the cause of the leak. A leak that is the result of trauma to the head usually is managed with placement of a lumbar drain and bed rest. When a CSf leak develops from inadvertent injury to the skull base at the time of surgery, but its recognition or onset is delayed, a CT sinus is typically requested in order to identify the defect site. On occasion, the defective skull base site may not be obvious on imaging studies and has to be identified in the operating room using a dye added to the CSF via a lumbar drain. Once identified, the leak can usually be repaired endoscopically. The benefit of the surgery is to not only stop the CSF leak, but also to remove the risk of an intracranial infection. The success of endoscopic repair of CSF leaks is generally over 90%.

Because of its prominent position on the face, the nose is one of the most injured areas of the head and neck. Whether from sports injuries, falls, or altercations, nasal fractures are a condition that otolaryngologist see quite often.

The typical history of nasal trauma followed by nose bleeding and subsequent nasal obstruction, strongly suggests nasal fracture. Physical exam findings of significant structural derangement can be diagnostic. In many instances, the external nasal deformity is not quite so obvious. In those cases, an X-ray or CT of the nose is warranted to more precisely evaluate the integrity of the bony and cartilaginous nasal structures.

Treatment of nasal fractures depends upon the severity of the injury and the wishes of the patient. If there is an open nasal fracture, with exposed bone and soft tissue, an operation to cleanse the wound and repair the fractures and close the soft tissue is warranted immediately to avoid severe deformity and infection. Most nasal fractures are closed, however. In cases of obvious deformity, closed reduction of the nasal fracture and external splinting within 10 to 14 days of the injury is indicated. After two weeks, the bones will be set in the fractured position and closed reduction will be ineffective. In a few cases of closed fractures not set within that two week window the patient will be left with a permanent nasal deformity. If the appearance of the nose is unsatisfactory and/or there is nasal obstruction as a result of the fractures, then a delayed surgical approach may be considered. In these instances, the nasal bones will have to be re-broken in a controlled fashion in the operating room and placed back in their native position. External splinting and possibly internal splinting as well are frequently employed for a week after surgery to allow the bones to set and healing to begin.

Anyone who has nasal trauma that feels that they may have fractured the nose, should be evaluated as soon as possible to rule out septal hematoma. This is a collection of blood beneath the covering of the cartilaginous nasal septum. If this condition is left untreated, it can result in severe infection in the soft tissue of the nose and/or destruction of the cartilaginous septum, which may cause a saddle nose deformity. Rapid, accurate diagnosis of nasal fractures allows planning of appropriate treatment and avoidance of unwanted complications.

EPISTAXIS INTRODUCTION

Epistaxis is defined as bleeding from the nostril, nasal cavity, or nasopharynx. Nosebleeds are due to the rupture of a blood vessel within the richly perfused nasal mucosa. Rupture may be spontaneous or initiated by trauma. Nosebleeds are rarely life threatening and are usually self-limited. Epistaxis is generally divided into anterior or posterior nosebleed, depending upon location in the nasal cavity.

Approximately 60% of the population will be affected by epistaxis at some point in time, with 6% requiring professional medical attention. The etiology of epistaxis is typically idiopathic (unknown), but it may also result from tumors, trauma, medication use, or after nasal/sinus surgery. Treatment of epistaxis may include the use of local pressure, vasoconstrictor nasal sprays, chemical or electric cautery, hemostatic agents, nasal packing, embolization, and surgical arterial ligation. There is no definitive protocol for the management of epistaxis and many factors including severity of the bleeding, use of anticoagulants, and other medical conditions can play a role in which treatment is utilized.

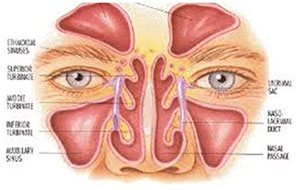

ANATOMY

The nasal cavity is extremely vascular. Blood is supplied via both the internal and external carotid arterial systems. The major blood arteries in the nasal cavity include the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries and the sphenopalatine arteries. Over 90% of nose bleeds occur in the anteroinferior nasal septum in an area known as Kiesselback’s plexus (named after Wilhelm Kiesselbach, a German otolaryngologist). Keisselbach’s plexus is located over the anterior nasal septum and is formed by anastomoses of 5 arteries:

- Anterior ethmoidal artery (from the ophthalmic artery) (Figure 1)

- Posterior ethmoidal artery (from the ophthalmic artery)

- Sphenopalatine artery (terminal branch of the maxillary artery) (Figure 2)

- Greater palatine artery (from the maxillary artery)

- Septal branch of the superior labial artery (from the facial artery)

Approximately 5% to 10% of epistaxis is estimated to arise from the posterior nasal cavity, in an area known as Woodruff’s plexus. Woodruff’s plexus is located over the posterior middle turbinate and is primarily made up of anastamoses of branches of the internal maxillary artery, namely, the posterior nasal, sphenopalatine, and ascending pharyngeal arteries. Posterior bleeds usually originate from the lateral wall and more rarely from the nasal septum.

ETIOLOGY

Causes of epistaxis can be divided into local causes (eg, trauma, mucosal irritation, septal abnormality, inflammatory diseases, tumors), systemic causes (eg, blood dyscrasias, arteriosclerosis, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia), and idiopathic (unknown) causes. Local trauma is the most common cause followed by facial trauma, foreign bodies, nasal or sinus infections, and prolonged inhalation of dry air. Tumors and vascular malformations are also possible causes of nose bleeds. Epistaxis is also associated with septal perforations (a hole in the dividing wall between the two sides of the nose).

Local Factors

Trauma to the lining of the nose and septum is a frequent cause of epistaxis. Nose picking and repeated irritation caused by the tips of nasal spray bottles commonly give rise to many anterior nose bleeds. Certainly, traumatic deformation and fractures of the nose and surrounding structures can cause bleeding. Another common cause of nosebleeds is due to infection and mucosal inflammation. Sinusitis, upper respiratory tract infections, and allergies can damage the respiratory epithelium to the point that it becomes friable and irritated. Additionaly, septal deviations, nasal fractures, and septal perforations can be a cause of irregular nasal airflow causing dryness and bleeding in some cases. Iatrogenic causes such as endoscopic sinus surgery, skull base surgery, and orbital surgery can also be a cause of severe epistaxis. Tumors of the nasal cavity, sinuses, and nasopharynx can also give rise to recurrent bleeding. In general recurrent unilateral epistaxis should be evaluated by endoscopy with or without imaging studies to screen for a tumor.

Systemic Factors

Hypertension, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, use of anticoagulants such as aspirin, clopidogrel, warfarin, and a variety of conditions causing vasculitis such as Wegener’s granulomatosis are common systemic factors associated with epistaxis. Epistaxis is also associated with blood dyscrasias, patients with lymphoproliforative disorders, immunodeficiency, and liver failure. Thrombocytopenia is associated with nasal bleeding. There can be spontaneous mucous membrane bleeding at platelet levels of 10-20,000. Platelet deficiency can also result from use of chemotherapy, antibiotics, malignancies, hypersplenism, and some drugs. Platelet dysfunction can occur in patients with liver failure, kidney failure, vitamin C deficiency and in patients taking aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (like ibuprofen).

Clotting factor abnormalities can result in frequent, recurring epistaxis. Bleeding disorders such as Von Willabrand’s disease (most common), Factor VIII deficiency (Hemophilia A), Factor IX deficiency (Hemophilia B), and Factor XI deficiency are all common primary coagulopathies. Additionally, patients with recurrent nosebleeds should be questioned about the use of complementary and alternative medicines such as Ginkgo Biloba and Vitamin E, which may increase their risk of bleeding.

TREATMENT

Direct pressure is usually effective for stopping epistaxis by applying pressure to Kiesselbach’s area on the anterior nasal septum. Nasal decongestants such as oxymetazoline (Afrin) or neosynephrine may also be used. Chemical cauterization with silver nitrate is also used for control of epistaxis unresponsive to local application of pressure. This can be done in the office with topical anesthesia. When these methods are not effective, anterior or posterior packing might be necessary. Packing can be absorbable or non-absorbable.

For complicated nose bleeds, another method of treatment is angiographic embolization of the internal maxillary artery. This procedure deploys a coil into the bleeding vessel to stop the flow of blood. It has a success rate of 71% to 95%, but the procedure carries risk of stroke, ophthalmoplegia, facial nerve palsy, and hematomas at the catheterization site. Also revascularization after embolization is not uncommon.

Direct surgical ligation is an alternative to embolization. Numerous approaches and techniques have been utilized and described. We generally employ an endoscopic approach for ligation of the sphenopalatine artery in the case of posterior epistaxis. In the case of refractory anterior epistaxis, we may use either endoscopic or open approaches.

CONCLUSION

In general, non-surgical treatments are effective for control of most cases of epistaxis. Nasal packing, chemical cautery, and use of nasal decongest sprays represent the first line of treatment for a majority of nasal bleeding. For recalcitrant epistaxis, embolization and surgical ligation is sometimes required. More recently, endoscopic approaches to the sphenopalatine artery and ethmoid arteries have been utilized with promising results.

Pediatric Sinusitis

In children, a common cold or viral infection is the most common event that may lead to a sinus infection. Also, foreign bodies such as a peanut, a raisin or a bead pushed into the nose may cause a nasal infection. When an infection begins, the lining of the nasal cavity may become swollen blocking the passage where normal sinus mucus drains. This results in a back up of mucus, which cannot get out. When this mucous remains in the sinus too long it can become infected.

SIGNS OF SINUSITIS

Many of the signs of childhood sinusitis are the same as the common cold. When the symptoms of a cold last longer than seven or ten days it is time to consider a sinus infection. Common sinus infection symptoms include:

- Halitosis (foul odor to the breath)

- Yellow or green nasal discharge

- Cough

- Headache (in older children)

- Facial pain or facial pressure

- Congestion

- Swelling around the eyes

HOW WILL DOCTOR KNOW IF SINUSITIS IS MY CHILD’S PROBLEM?

In addition to a thorough history and physical exam, the physician may order an X-ray or CT of the sinuses to make a diagnosis of sinusitis.

HOW WILL MY CHILD BE TREATED?

Antibiotics are the primary medication for the treatment of sinusitis. Other medications include:

- Decongestants to decrease mucus

- Mucolytics to thin the mucus

- Steroid nasal sprays to reduce nasal swelling

It is very important to finish all of the medication even if the symptoms of the infection seem to have gone away.

Sometimes the medications do not completely clear away the infection. The child then requires a re-evaluation.

Enlargement of a child’s adenoids, which are located in the back of the nose, may be a cause of sinusitis. If your child has frequent sinus infections and is a “mouth breather”, is unable to breath through his/her nose or snores loudly, then he/she should be checked for large adenoids. Your physician will be able to help make this diagnosis based on your child’s symptoms. Examination of the child’s nose and the use of x-rays are also important in looking for large adenoids.

When your child continues to have sinus infections despite medical management, your physician will consider obtaining further studies such as tests to rule out other factors such as allergy, cystic fibrosis, ciliary dyskinesis, and immunodeficiency. In addition, your physician may recommend surgical treatments such as adenoidectomy and edoscopic sinus surgery.

Introduction:

A stuffy nose, known as nasal obstruction, is a very common problem. Patients with nasal obstruction have trouble breathing through their nose. This can force mouth breathing, which can lead to dry mouth and snoring or sleep disturbance.

Nasal obstruction can be caused by a number of problems. Common causes include allergic rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, and non-allergic rhinitis. Often narrow nasal airway passages are the result of anatomic deviations of the septum and turbinates. In addition, a deviated septum and turbinate hypertrophy may be a major factor in recurrent acute sinusitis. This should be a consideration in patients who have recurrent sinus infections every year, but who clear for periods of time with appropriate treatment.

Nasal Septum:

The nasal septum is a normal structure inside the nose that divides the nose into right and left sides. A deviated septum is a septum that is not relatively straight.

The turbinates are scrolls of bone, covered by mucous membrane, that originate from the lateral wall of the nose. They usually come close to the septum, but there is some space, which allows airflow through the nose.

The nasal septum is made of cartilage and bone and is covered by a thin membrane called mucosa. Mucosa acts as skin inside the nose, providing protection for the underlying tissues. It also keeps the inside of the nose moist and produces mucus to facilitate trapping small particles from the air you breathe.

When the septum is deviated, one or both sides of the nose can become blocked. In these instances, surgery can help to correct the deviation and improve airflow.

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of a deviated septum can be made by your ENT physician. He/she will perform a thorough evaluation of your symptoms and will examine your nose. You may undergo an in-office procedure called nasal endoscopy to diagnose the cause of your nasal obstruction. A deviated septum can also be seen on a CT scan, which may help to further define nasal anatomy and rule out any occult sinus disease.

Surgery:

Surgery to correct a deviated septum is called a septoplasty. Reduction in the size/shape of the turbinates is called turbinoplasty. These two procedures are often done together to get the best result possible with respect to nasal airflow. The surgery is performed as an outpatient procedure while the patient is under general anesthesia. A small incision is made on one side of the septum and the mucosa is elevated off the cartilage and bone. Some portion of the bony and cartilaginous septum will then be removed. The mucosa is replaced. The inferior turbinates may be addressed by performing a submucosal resection of the soft tissue of the turbinate, using a small microdebrider blade. You may have a small piece of packing in you nose after surgery. You will start rinsing your nose with saline solution the day after surgery. This will loosen clots and mucus and allow the tissues to heal well. The risks of septoplasty and turbinoplasty are as follows:

- Bleeding, infection, intranasal adhesions (scars), transient hypesthesia (numbness), and allergic reaction are common problems of moderate consequence. All bleeding at the time of surgery will be stopped, but some light bleeding may continue for a day or two after surgery. Antibiotics will be given prior to the start of the operation and after surgery for a period of time to prevent infection. If severe, intranasal adhesions may need to be later lysed. Hypesthesia will usually fade with time. Allergic reactions will be treated as required.

- Patient dissatisfaction and new nasal deformity are possible. There are many factors that contribute to nasal obstruction which may persist despite successful correction of a deviated nasal septum. In addition, occasionally, coexisting medical illnesses or excessive manipulation can lead to inadequate healing, resulting in new displacement or nasal collapse.

- Postoperative septal perforation occurs about 5% of the time. This complication usually does not result in functional impairment, but may require a septal button or surgical correction.

- Rarely, septoplasty can result in injury to the base of the skull and lead to cerebrospinal fluid leak., olfactory nerve injury, pneumocephalus (air in the skull), intracranial hemorrhage, and/or injury to the frontal lobe of the brain. A secondary intracranial infection could occur as a result of injury to this area of the skull. Treatment will consist of placement of a lumbar drain for CSF leak, hospitalization and possibly a surgical repair of the leak.

Postoperative Care:

You can expect to have pain, fatigue, nasal stuffiness, and mild nasal drainage after your surgery. Pain is usually well controlled with oral pain medications. The stuffiness of your nasal cavity will gradually subside over one to two weeks. You may have drainage of some blood and mucus after surgery, which is normal. Your doctor will see you at one week follow up to assess the healing process and give you instruction on any further treatments necessary.

What is the most common symptom of a “sinus infection”? If you are like most people, you most likely think of sinus headache as a primary problem with sinus infection. Both sinusitis and headaches are very common problems. Because the sinuses are located in the front of the head, where most headaches occur, there is bound to be a lot of overlap between these two diagnoses.

Let’s begin with a headache that is related to sinus disease. This occurs in the setting of a case of acute rhinosinusitis (ARS). ARS is defined as sinusitis symptoms and physical findings lasting less than four weeks. In the setting of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis, there is purulent drainage, which is comprised of large numbers of inflammatory cells responding to the presence of high bacterial counts in static mucus in the paranasal sinuses. This inflammatory process triggers vasodilation and irritation of nerves that lie just beneath the surface of the lining of the sinuses and nasal cavity. These processes trigger the pain response that we call sinus headache.

The difficulty in diagnosis comes when someone has “sinus headache”, or headache located in the face area, without other symptoms of nasal or sinus disease, such as nasal obstruction or discolored discharge. Often, these patients have some other cause of headache, such as migraine headache. This is especially true of patients who are having recurring bouts of “sinus” which are essentially unresponsive to antibiotics. In many cases, a trial of a migraine headache medicine will completely eliminate the patient’s symptoms.

Confusion about sinusitis and headaches is common and understandable. These conditions require a thorough medical history and head and neck physical exam. In addition, you may need nasal endoscopy, sinus CT or both to confirm your diagnosis. Consultation with you ENT physician can help differentiate whether you need treatment for sinusitis or headache. Call 205-980-2091 today to make an appointment

What is the most common symptom of a “sinus infection”? If you are like most people, you most likely think of sinus headache as a primary problem with sinus infection. Both sinusitis and headaches are very common problems. Because the sinuses are located in the front of the head, where most headaches occur, there is bound to be a lot of overlap between these two diagnoses.

Let’s begin with a headache that is related to sinus disease. This occurs in the setting of a case of acute rhinosinusitis (ARS). ARS is defined as sinusitis symptoms and physical findings lasting less than four weeks. In the setting of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis, there is purulent drainage, which is comprised of large numbers of inflammatory cells responding to the presence of high bacterial counts in static mucus in the paranasal sinuses. This inflammatory process triggers vasodilation and irritation of nerves that lie just beneath the surface of the lining of the sinuses and nasal cavity. These processes trigger the pain response that we call sinus headache.

The difficulty in diagnosis comes when someone has “sinus headache”, or headache located in the face area, without other symptoms of nasal or sinus disease, such as nasal obstruction or discolored discharge. Often, these patients have some other cause of headache, such as migraine headache. This is especially true of patients who are having recurring bouts of “sinus” which are essentially unresponsive to antibiotics. In many cases, a trial of a migraine headache medicine will completely eliminate the patient’s symptoms.

Confusion about sinusitis and headaches is common and understandable. These conditions require a thorough medical history and head and neck physical exam. In addition, you may need nasal endoscopy, sinus CT or both to confirm your diagnosis. Consultation with you ENT physician can help differentiate whether you need treatment for sinusitis or headache. Call 205-980-2091 today to make an appointment